- Man, oh man. Possibly the coolest website ever and more chemical ecology than I know what to do with (and here's another). h/t OrchidGrownMan from Biofortified

- Open source Legos for grownups. Can I have a microtractor? or a microcombine? or a dimensional sawmill? Pleeeease?

- More scientific sour grapes. Why won't grad students sacrifice their entire careers to do what we think is important?

- And, as always, maps! This time, watch agriculture spread. h/t Seed.Feed.Food

Showing posts with label geography. Show all posts

Showing posts with label geography. Show all posts

Wednesday, April 27, 2011

Wednesday Links

Saturday, January 22, 2011

Weekend Short Stories

Some pretty cool links for your weekend:

Jurassic Park beer:

Fossil Fuels Brewing Co. makes beer with an Eocene-era yeast, formerly encased in a 45 million year old chunk of amber! Incredible, but apparently true. Viable Bacillus spores were discovered first in 25-40 million year old amber by Raul Cano (these spores are so tough you can't kill them with an autoclave). He then founded a startup (Ambergene) with the hopes of discovering ancient antibiotics (this was back during the natural products craze - when pharma companies sent explorers to coral reefs, rainforests and geothermal hot pools to find new biologically-active chemicals. Now, most just do combinatorial synthetic chemistry). The company failed, but when you can't make money, make beer! h/t: AncientFoods

Living off the land:

The Resilient Gardener teaches us how to be subsistence farmers in a temperate climate: corn, potatoes, beans, squash and eggs. h/t: Living the Frugal Life

A reason to like kale:

Organisms can optimize their fitness by reproducing early when times are good and holding back and focusing on survival when times are bad (if your population is about to experience an involuntary bottleneck, offspring born afterwards will contribute proportionally more genes to the population). This Week in Evolution discusses the reproductive advantages that an organism would accrue if it could delay reproduction specifically in times of environmental stress.* In PLoS one, Will Ratcliff cites examples of creatures from yeast to rats showing increased longevity (and delayed reproduction) when exposed to minor environmental stresses (calorie restriction, temperature stresses, low dose toxins).** They hypothesize that the consumption of "famine foods" (e.g. low calorie and nutrition and moderate toxicity) would be an effective cue for an organism to switch to survival mode.

and Maps!

The U.S. by last names, but why no Italians?***

An incredible morphing cartogram displays everything

The world according to Americans

Intriguing, yet almost impenetrable

Jurassic Park beer:

Living off the land:

The Resilient Gardener teaches us how to be subsistence farmers in a temperate climate: corn, potatoes, beans, squash and eggs. h/t: Living the Frugal Life

A reason to like kale:

Organisms can optimize their fitness by reproducing early when times are good and holding back and focusing on survival when times are bad (if your population is about to experience an involuntary bottleneck, offspring born afterwards will contribute proportionally more genes to the population). This Week in Evolution discusses the reproductive advantages that an organism would accrue if it could delay reproduction specifically in times of environmental stress.* In PLoS one, Will Ratcliff cites examples of creatures from yeast to rats showing increased longevity (and delayed reproduction) when exposed to minor environmental stresses (calorie restriction, temperature stresses, low dose toxins).** They hypothesize that the consumption of "famine foods" (e.g. low calorie and nutrition and moderate toxicity) would be an effective cue for an organism to switch to survival mode.

"Plants high in insect-repelling toxins might be an example of such "famine foods", even if some modern humans have developed a taste for kale, coffee, or hot peppers. These plant toxins might have small negative effects on our health. But, if our bodies respond to the information carried by those toxins -- famine! population decline likely! delay reproduction! -- then those negative effects may be outweighed by the health benefits of setting our hormone levels etc. to values optimized for longevity rather than reproduction."

and Maps!

The U.S. by last names, but why no Italians?***

An incredible morphing cartogram displays everything

The world according to Americans

Intriguing, yet almost impenetrable

* Not to be confused with my long-favorite, TWIS.

** Whom I played in a band with out of the very-Davis J St Coop

*** I assume this map is more biased by the redundancy by which different cultures reuse the same names than the spatial scale at which the immigrant populations currently dominate.

Ratcliff, W., Hawthorne, P., Travisano, M., & Denison, R. (2009). When Stress Predicts a Shrinking Gene Pool, Trading Early Reproduction for Longevity Can Increase Fitness, Even with Lower Fecundity PLoS ONE, 4 (6) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006055

Cano, R., & Borucki, M. (1995). Revival and identification of bacterial spores in 25- to 40-million-year-old Dominican amber Science, 268 (5213), 1060-1064 DOI: 10.1126/science.7538699

Ratcliff, W., Hawthorne, P., Travisano, M., & Denison, R. (2009). When Stress Predicts a Shrinking Gene Pool, Trading Early Reproduction for Longevity Can Increase Fitness, Even with Lower Fecundity PLoS ONE, 4 (6) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006055

Cano, R., & Borucki, M. (1995). Revival and identification of bacterial spores in 25- to 40-million-year-old Dominican amber Science, 268 (5213), 1060-1064 DOI: 10.1126/science.7538699

Wednesday, October 13, 2010

Holland Infographics

I just got back from Wageningen, NV.* The Netherlands is a very wet country, but we had excellent weather and I had a lot of fun meeting everyone at the headquarters. And such a cool town! Same population size as Ithaca or Davis, but with a denser downtown, older buildings and a much more bike-friendly infrastructure...

I just got back from Wageningen, NV.* The Netherlands is a very wet country, but we had excellent weather and I had a lot of fun meeting everyone at the headquarters. And such a cool town! Same population size as Ithaca or Davis, but with a denser downtown, older buildings and a much more bike-friendly infrastructure...

Sunday, June 6, 2010

Gardening a Forest

I grew up (mostly) in an old farmhouse in Delaware. The three foot thick stone walls that make up the core of the house are probably 200+ years old, and from the basement, you can see that the main floor is supported by whole, rough-hewn tree trunks. The farmland was bought up and developed before I was born, but field stone walls and small building foundations are still present, scattered in the surrounding acres of private and state land.

I grew up (mostly) in an old farmhouse in Delaware. The three foot thick stone walls that make up the core of the house are probably 200+ years old, and from the basement, you can see that the main floor is supported by whole, rough-hewn tree trunks. The farmland was bought up and developed before I was born, but field stone walls and small building foundations are still present, scattered in the surrounding acres of private and state land.Mirroring a century-long trend that has occurred throughout the Eastern U.S., the original farm was abandoned and now-maturing secondary forests grew up in its place. The U.S. now has more forest than anytime since European colonies were established.

The forest on and around my parents' property is in decline. The suburbanites have been neatening up the woodlots that snake between all their plots, cutting down ugly and dangerous trees and preventing the re-establishment of many seedlings. Many of the largest trees are falling now. The pro arborists say the giant boulders half-hidden in the soil compromise the trees' hold, and I imagine the loss of their neighbors increases windthrow.

Tuesday, June 1, 2010

New running route, New plants to learn

I just went for a walk along the country road I now live off of (this one's paved). It'll make for a nice running route. It's lined by active ag fields (some run by the University) instead of fallow pastures and has a number of wildflowers and weeds that I already don't recognize. There are also at least 4 grasses, which I won't even attempt to ID unless I'm given reason to.

I just went for a walk along the country road I now live off of (this one's paved). It'll make for a nice running route. It's lined by active ag fields (some run by the University) instead of fallow pastures and has a number of wildflowers and weeds that I already don't recognize. There are also at least 4 grasses, which I won't even attempt to ID unless I'm given reason to.I was captivated by the tall, rippling roadside grasslands I saw in southern Virginia this past weekend (they reminded me of my childhood Plains - there were even some clumps of prickly pear!). I was all ready to post a rant blasting PA for their ugly, ragged mowed highway corridors when I climbed north into Harrisonburg and the tall grasses gave way to short ones and scrubyness - so I guess it's not just obnoxious landscaping's fault. I don't know if the soil/climate changed or the southern end of 81 is heavily seeded by the local pasture grasses (the ecoregion map provided few clues) but I'll hopefully have the presence of mind next time I'm down there to grab some flowers to ID.

I have the means: a 1935 copy of Manual of the Grasses of the United States.

Monday, February 15, 2010

U.S. Regions via Facebook

I'm completely fascinated by regional idiosyncrasies of ecology and culture. Every time I hear someone comment about how they associate some typical personality with some part of the country, I can't help but pin them down and try to figure out exactly what their impression is and how they came up with it.

Appropriately, Peter Warden created a map of the U.S. based on the connectivity of Facebook friends. He found that friendships in the U.S. form 7 major clusters, which he dubs...

Stayathomia

The Northeast and Midwest, where people die in the town they were born. People mostly are friends with people in their own town and the next one over.

Dixie

Same as above but as a separate cluster (which doesn't include southern Florida). People are very likely to have friends in Atlanta.

Greater Texas

Includes Missouri and the Gulf Coast. People are very likely to have friends in Dallas.

Nomadic West

People are very likely to have friends in all kinds of small and large towns throughout the entire western half of the country.

Mormonia

A little cluster inside the above, located appropriately.

Socalistan

LA is the hub of California, where Californians tend to be friends only with Californians (no surprise here).

Pacifica

People in Seattle apparently never go anywhere besides Seattle.

h/t: Edible Geography, PSFK

Appropriately, Peter Warden created a map of the U.S. based on the connectivity of Facebook friends. He found that friendships in the U.S. form 7 major clusters, which he dubs...

Stayathomia

The Northeast and Midwest, where people die in the town they were born. People mostly are friends with people in their own town and the next one over.

Dixie

Same as above but as a separate cluster (which doesn't include southern Florida). People are very likely to have friends in Atlanta.

Greater Texas

Includes Missouri and the Gulf Coast. People are very likely to have friends in Dallas.

Nomadic West

People are very likely to have friends in all kinds of small and large towns throughout the entire western half of the country.

Mormonia

A little cluster inside the above, located appropriately.

Socalistan

LA is the hub of California, where Californians tend to be friends only with Californians (no surprise here).

Pacifica

People in Seattle apparently never go anywhere besides Seattle.

h/t: Edible Geography, PSFK

Saturday, January 30, 2010

Tuesday, November 17, 2009

"Eating Animals"

What I've heard to date suggested he would be an irrational extremist, but on the radio at least, he was calm, logical and (when it came to the economics and logistics of agriculture) accurate.

He asserted that the treatment of animals in industrial agriculture falls below the ethical standards of all people, that people would be revolted if they actually understand how animals are treated and that the only solution is to become a vegetarian (as low-intensity agriculture isn't productive enough to keep 6 billion people in beef and chicken).

A lot of people seem to be freaking out about his book, but his appearance on the radio was reasoned, consistent and offered one possible answer to my question.

He said that he's never met someone who was a proponent of factory farms, but I think that may just reflect his social circles. I'm all for legislating the humane treatment of animals, but I don't think that's mutually exclusive with high intensity animal ag.

Saturday, November 14, 2009

What's your Gardening Geography? [UPDATED]

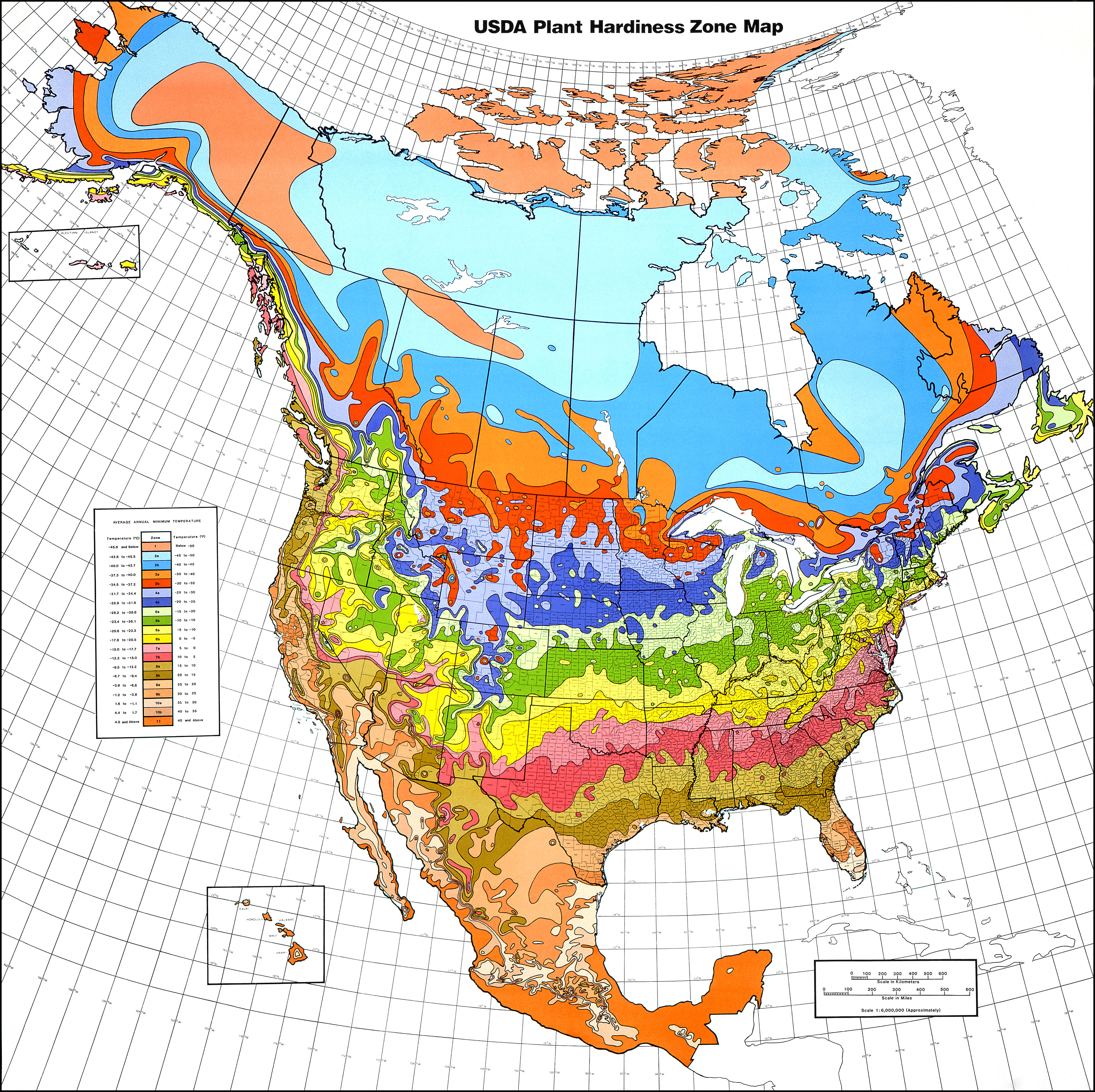

If you're like me, you grew up consulting the USDA hardiness zone map to forecast what plants could be successfully grown in your climate. These zones are defined by the average minimum temperatures experienced in a given region of the country. E.g. plants that are hardy (can survive) to 15-20F could be expected to survive in zone 8 cities such as Seattle or Dallas. An updated map is currently in the works to reflect the recently warmer climate and the extent to which major urban areas retain heat.*

If you're like me, you grew up consulting the USDA hardiness zone map to forecast what plants could be successfully grown in your climate. These zones are defined by the average minimum temperatures experienced in a given region of the country. E.g. plants that are hardy (can survive) to 15-20F could be expected to survive in zone 8 cities such as Seattle or Dallas. An updated map is currently in the works to reflect the recently warmer climate and the extent to which major urban areas retain heat.*You may have noticed that very different climates are included within the same zones. As an extreme, Wikipedia points out that both the Shetland Islands and southern Alabama sit on the border of zones 8 and 9. Hardiness zones don't account for numerous critical factors, including average high temperatures, rainfall patterns, humidity, probability of extremely cold temperatures and the protective effect of snow cover.

Such fine-scale differences in microclimate are influenced by both topology and regional weather patterns and account for much of the regional variation in ecosystems. The EPA currently has a project (which I'm fairly obsessed with) that is working to map and define ecoregions across the United States by geography, climate and native vegetation. It's an awesome resource for native gardeners or anyone who wants to appreciate their local wildernesses on a more holistic, "systems" level.

Such fine-scale differences in microclimate are influenced by both topology and regional weather patterns and account for much of the regional variation in ecosystems. The EPA currently has a project (which I'm fairly obsessed with) that is working to map and define ecoregions across the United States by geography, climate and native vegetation. It's an awesome resource for native gardeners or anyone who wants to appreciate their local wildernesses on a more holistic, "systems" level.Sunset Books has been including more than average minimum temperature in their gardening recommendations for years. Originally specializing in the diverse gardening habitats of the Pacific and Intermountain West, they now include specific gardening recommendations across the U.S.

According to their Plant Finder, Boston is hot and humid enough in the summer (yet not too cold in the winter) for a native North American palm tree. Who would have thought?

UPDATE: here's the provisional updated hardiness map. yikes!

UPDATE: here's the provisional updated hardiness map. yikes!*I keep hearing reference to some study that predicts global warming will bring Virginia temperatures to upstate New York within a few decades. As someone who loves cold, snowy weather, I desperately hope this isn't true!

Saturday, October 10, 2009

Another Kink in Eating Local

Somehow I missed this article from last year. In it, two professors from Carnegie Mellon describe how despite the enormous distances that modern foods are shipped, transportation as a whole accounts for only 11% of the total greenhouse gas emissions produced by agriculture. Delivery of finished food products to retail stores accounts for only 4% of the total emissions. They conclude that "buying local" is less effective in lowering our carbon footprint than shifting from red meat and dairy to less carbon-intensive poultry, fish and veggies.

Somehow I missed this article from last year. In it, two professors from Carnegie Mellon describe how despite the enormous distances that modern foods are shipped, transportation as a whole accounts for only 11% of the total greenhouse gas emissions produced by agriculture. Delivery of finished food products to retail stores accounts for only 4% of the total emissions. They conclude that "buying local" is less effective in lowering our carbon footprint than shifting from red meat and dairy to less carbon-intensive poultry, fish and veggies.The greater efficiency of concentrating agriculture in the best locations is reflected in Jeremy's post at Ag Biodiversity. Check out his stunning maps that illustrate the global distribution of farming in 1995 versus the concentration of agriculture in only the best locations (it's not clear if this is hypothetical or actual). Like any other industry, agriculture is most efficient when located where the competitive advantages lie (e.g. good soil, weather and cheap and available labor). Unlike other industries though, I think agriculture may be an industry that we should sacrifice some efficiency in order to maintain the robustness of a distributed network. No one will starve, overthrow their government or start a war if political or natural obstacles suddenly cut them off from iPod factories on the other side of the world...

I don't have the time (or probably the qualifications!) to dig into the authors' methods to see exactly how they calculated all this, but it's a good reminder of how unintuitive complex systems can be. It's easy to suggest aesthetically-pleasing ideas such as buying local, but the devil is in the details. As James points out, there's not even close to enough land surrounding major population centers like NYC or Philly to feed all the inhabitants within a "local" number of food miles - let alone the fact that very few crops are grown in many of these regions to begin with (e.g. pretty much just dairy in upstate NY). It's often more efficient to grow crops year-round in sunny Arizona or California, or in the deep soils of the Midwest (and ship them thousands of miles) than grow them locally in cool, short summers on rocky soil.

As a big fan of New Urbanism, I'd be happy to vote for legislation that encourages dense, mixed zoning with lots of subsidized parks (including garden plots and farms) in and around cities, but that's more a statement of aesthetic preference than of effective conservation. I think we would benefit from a more clear understanding of not only the facts involving the environmental and social impacts of modern agriculture, but also our personal motivations for our beliefs.

If some sort of concentrated feed lot system turns out to be the most environmentally-friendly form of beef production, would you advocate it?

Monday, August 24, 2009

Chesapeake Oyster Reef Restoration

It sounds like they may be making some progress at least. Oysters previously formed extensive reefs that filtered the water and supported much of the ecosystem. These reefs previously existed as giant piles of empty shells that oyster larvae would settle (and eventually die) on, leaving their shells behind. A research project has been able to establish a few new reefs by dumping huge numbers of oyster shells into piles at the mouths of rivers. One of the key discoveries was that these piles had to be very high to prevent being covered by mud.

Hopefully this strategy will continue to work as they try it around the bay.

Saturday, August 1, 2009

Vacation in Zone 63d

Bioregionalism is the celebration of the unique cultural and ecological features of small geographic areas - and is the philosophical basis of Buy/Eat Local campaigns.

Bioregionalism is the celebration of the unique cultural and ecological features of small geographic areas - and is the philosophical basis of Buy/Eat Local campaigns.I love the EPA Ecoregion project. Follow the link to the most detailed (IV) ecoregion map and click on your favorite part of the country. There you'll find your local ecoregion as defined by climate, soil type and native vegetation.

The drive south from upstate New York to the Atlantic beaches of Delaware took me through the jigsaw geography of the Appalachians, accompanied by dozens of ecoregion transitions. Hugging the southeastern foothills of the Appalachians, the Piedmont plateau stretches from New Jersey to Alabama. This plateau then falls steeply along the Fall line to the Atlantic Coastal Plain, which gently slopes into the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Mexico.

Delaware is a low, flat and marshy place. It exists almost entirely within the Middle Atlantic Coastal Plain (zone 63). Zone 63 is the middle section of the full Atlantic Coastal Plain, includes all of the Delmarva Peninsula and is most prominent in the eastern Carolinas. The beaches and bays of Delaware's short Atlantic Coast (as opposed to it's long border with the Delaware Bay) belong specifically to zone 63d, the "Virginian Barrier Islands and Coastal Marshes."

Driving south on DE-1 quickly removed me from the highly-populated Philadelphia metropolitan area to the state's more rural majority. Below the capital of Dover and Miles the Monster, Delaware begins to stretch into the ecological South. The flat landscape fragments into a fine-grained patchwork of corn, soybeans, woodlots and wetlands, speckled with little evangelical churches and beach-oriented tourist traps. In between small towns, wide creeks slowly seep out towards the tidal marshes of the Delaware and Chesapeake bays.

Landmarks in this part of the state carry unique names that often seem to allude to a more difficult past: Hardscrabble, Old Furnace, Muddy Branch, Gumboro, Skeeter Neck, Black Hog Gut, Slaughter Beach and the Murderkill River. Neck, gut, branch and beach are landform-specific nouns that are frequently encountered along this drive. Aside from the legendary fisheries of Maryland's Eastern Shore (blue crabs!), this region was originally best known for peaches (Delaware's state flower), melons and other warm climate high-value crops. Today, it's probably best known for chicken factories. Much of this soggy peninsula was never really inhabited, at least following European colonization. To some extent this may be changing as the coastlines are developed for resorts and vacation homes.

Trap Pond State Park is one of many great, small parks scattered within an easy drive of Peninsula resort towns. It's in many ways typical of Southern coastal forests. It's a swampy bottomland, topped by strong straight loblolly pine, mixed with oaks, gums and the smooth and sinewy, lichen-splattered limbs of understorey holly (Delaware's state tree). I was there for it's atypical feature: possibly the most northern natural stand of baldcypress trees. The first image is one most usually associated with alligator-filled bayous, the main haunt of these trees. The second is an up close and personal view of the trees' "knees." The third image is as close as I could get to an "island" of baldcypress trees in the middle of the lake.

See the frog in the last picture? There were a few that appeared to be adults, and hundreds of (juveniles?) less than an inch long, that scattered underfoot along parts of the trail. There were also some large, colorful beetles and butterflies (and a large snapping turtle diverting traffic on our way back to the beach). Subtropical forests like this are also known for mosquitoes, biting flies, ticks and chiggers. Thankfully, I encountered few of these.

My week over and full of crabs and vitamin D, I headed back north.

For many Delawareans, The Canal (along with the "vertical" section of the Mason-Dixon Line) cuts off the top of Delaware's most populated (of 3) counties, and associates them with the Urban Northeast, and forms a psychological barrier between them and the long, slow, punctuated gradient through "Slower, Lower [Delaware]" to the cultural South.

I'm always fascinated by such arrogant local nationalism. Growing up along the Mason-Dixon Line, I was accustomed to people aggressively asserting whether they belonged to the "North" or "South." At the extremes, I've listened to Georgians derogatorily refer to anyone north of South Carolina as yankees, and have heard that Bay Staters tend to proudly retain the same word only for their brethren who have lived in New England for a sufficient number of generations.

At any rate, crossing north on the Canal bridge lifts you above the Middle Atlantic Coastal Plain and presents a view of the rolling hardwood forests that define the Piedmont Uplands of southeast PA. Shortly after crossing the Canal, I lost sight of formerly plentiful roadside southern pines - likely a result of land history, not climate.

Just a little farther north, where I-95 briefly traverses Delaware, the state's largest city sits on the marshes of the Delaware Bay. Wilmington is a small, successful city, powered by highly-subsidized bank and chemical companies and surrounded by the converted rural estates of 19th-century industrialists and the extensive suburbs that voraciously metastasize across all farmland within reach of the BosWash megalopolis. One or two highway exits brought me back up onto the Piedmont, up through the rippled Appalachians and back to the Eastern Great Lakes and Hudson Lowlands.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)